The PlayPump is the central case-study in my PhD thesis ‘Radical Plumbers and PlayPumps – Objects in development’ (2011), which looks critically at the relationship of first world audiences and developing world users via designed objects. The ‘radical plumbers‘ in my thesis title refers to antiprivatisation activists in South Africa who reconnect the water supplies of poor people cut off for nonpayment.

In my thesis (download PDF) I analyse the PlayPump at length, and it is that document you should consult for all my evidence and arguments about the project. On this page of my site is a brief background introduction to the rise and fall of the project, followed by a short discussion of some of the points from my thesis, some of my presentations on the PlayPump, and a reference section with links to supporting documents and other critical information about the project.

Background

The PlayPump is a children’s roundabout that pumps water. The basic system was invented by water engineer Ronnie Stuiver in South Africa in 1989, and then modified and popularised by a former advertising executive, Trevor Field. Field added an elevated water tank to the design, to capture water from children’s play for adults to draw later, and billboards, to be rented out to raise money for the installation and maintenance of the system. The PlayPump’s promise of essential work accomplished through children’s play, and of ‘sustainability’ via its advertising-funded maintenance system, was highly attractive to the press and to funders, and images of the system proved remarkably effective in attracting support for the project internationally.

After winning a World Bank Development Marketplace Award in 2000, and through a series of positive reviews in the international press, the project accelerated rapidly. Former US President Bill Clinton wrote about it an editorial for the New York Times in 2006, and First Lady Laura Bush referred to it in her address to the 2007 National Design Awards at the Cooper Hewitt Museum. The UK company Global Ethics brought out a bottled water brand, One Water, to help fund the PlayPump, and the Case Foundation in the US set up the fund-raising organization PlayPumps International. PlayPumps International ran very successful campaigns to gather donations online, organizing major concert tours and celebrity endorsements. In 2006 the Case Foundation partnered with USAID and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief to present PlayPumps International with a grant for US$16.4 million, intended as the first installment in a commitment to raise US$60 million to roll out PlayPumps across southern Africa.

But in 2009, support for the project began to decline sharply. Critical press reviews and blog posts, and previously unavailable reports on the PlayPump by UNICEF (2007), and by the Mozambiquan government (2008) identified a number of problems with the project on the ground. Children’s play was not an adequate source of input to the pump, so adults had to turn the roundabout by hand, and they found this much less efficient than a hand pump’s lever. Users were also dissatisfied, particularly outside South Africa, with the amount of time it took for faults to be repaired. In addition, a lack of advertising uptake on the PlayPump was identified, with many billboards blank, indicating that funds were not coming in for maintenance. The Case Foundation withdrew from the project and dissolved PlayPumps International in early 2010. Field’s South African company is still in operation.

The dissatisfaction of users of the system was compounded by the fact that, contrary to the impression created by the PlayPump’s publicity, the project did not bring water where there was none before, but were usually placed on existing boreholes, replacing hand pumps. Where users had hand pumps before, they preferred these, and complained about a lack of consultation in their choice of technology. PlayPumps are also much more expensive for funders than conventional handpumps. As a position statement on PlayPumps by the charity WaterAid noted in 2009, at a cost to the donor of US$14,000 for a single PlayPump, four conventional hand pumps could be installed.

Discussion

How could a project with such high levels of support from the press, design institutions, state and private funders, and the public in the ‘first world’, turn out to be so unpopular with the intended beneficiaries of the project in the ‘developing world’? This difference between the PlayPump as perceived by audiences in Europe and the United States and the experience of users of the technology in Southern Africa formed the crux of my investigation for my thesis. It identified the risk that objects which told compelling stories to these removed audiences (often in pursuit of funding) might be advanced regardless of how well they worked for the people using them.

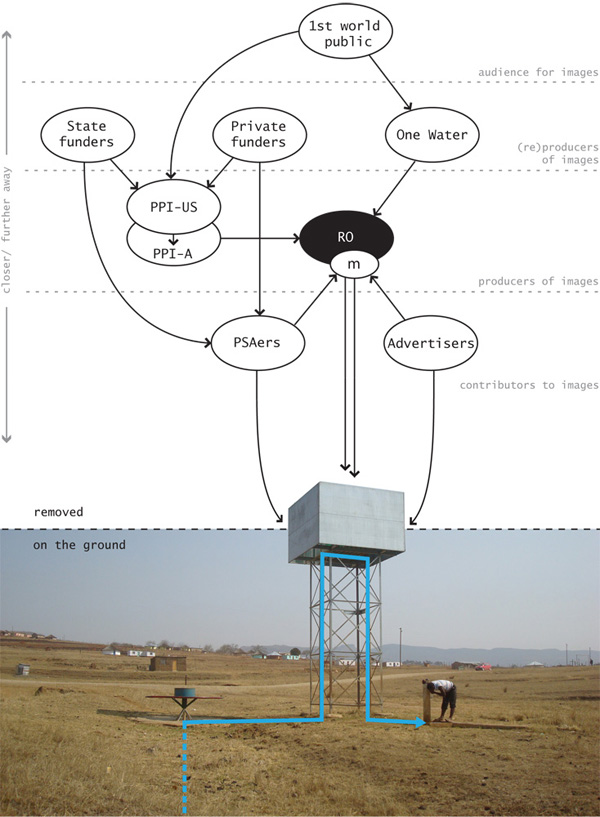

I created the diagram below to help understand the relationship between these audiences and users, as mediated by the different bodies involved with the PlayPump. The PlayPump in this diagram is understood as both a discrete, particular object on the ground somewhere (the lower part of the diagram) and as a larger overlying system for funding, maintenance and image distribution (key: PSAers = public service advertisers; RO = Roundabout Outdoor, original producers of the PlayPump; PPI-US = PlayPumps International (US), PPI-A = PlayPumps International’s African body; M = maintenance, indicating how billboard rentals were meant to fund the maintenance of the pump).

I imagined the boundary between these two zones, represented by the horizontal dashed line in the diagram, as a type of ‘screen’. Looking ‘down’ from the top of my diagram, audiences see, not the failed technology on the ground, but idealized images projected there by the producers of and partners to the project. What these images played on was a few key propositions: the PlayPump as a character in positive, non-conflictual narratives around aid and access to resources; as an innovative, novel object; as the ‘magic roundabout’ as it was frequently described in the press (because it can produce goods without labour); and as mobilizing the notion of ‘child’s play’, a pun also often used in the press to describe both the simplicity and mode of operation of the pump.

The PlayPump apparently literalises the metaphor of ‘child’s play’: a simple idea that just works, and which in this case actually relies on children’s play. Through the PlayPump, two apparently opposite ideas, (adult) ‘work’ and (child’s) ‘play’ are collapsed. PlayPumps International’s strap line was ‘Kids play. Water pumps!’, their punctuation emphasizing the separation of these two actions – work happens as an effortless byproduct of play. The idea of play is encoded into the technology itself: the roundabout is an iconic playground object for Western viewers. Its presence persuades viewers that play, and therefore pleasure, must characterize the user’s interaction with the pump. It has a self-evident logic to it that has made for a near-universal interpretation, from a distance, that the PlayPump works the way it is supposed to. To picture adults pushing the roundabout around by hand as a repetitive chore requires a leap of imagination; the more potent image it suggests is the one the PlayPump’s producers are glad to reinforce, of children playing.

The PlayPump is most likely perceived of as ‘magical’ because it creates the appearance of work accomplished without human labour. The apparent innovation of the PlayPump is to have the work of water pumping accomplished as a byproduct of children’s play. The design of the system, with the pumping mechanism hidden inside the roundabout, and all connections between the roundabout and the water tank concealed beneath the ground, creates the illusion of roundabout and pump operating independently. Coca-Cola during their partnership with Roundabout Outdoor described the PlayPump as “a children’s roundabout with a hidden agenda to provide energy for a borehole pump” (Coca-Cola c. 2000). This “modern-day alchemy” converts “the energy of children cavorting on a simple playground merry-go-round into clean water” (Everline 2007). It transforms work into play.

The PlayPump takes its place amongst other magical objects in the European folk-story tradition that produce goods without labour: salt-grinders, cooking pots, axes and harps. Walt Disney portrayed a version of the German fairy-tale ‘The Magician’s Apprentice’ in Fantasia (1940), with Mickey Mouse as the apprentice unable to keep control of a magical broom he attempts to have do his work for him – as is usually the moral with these stories. As with the figure of speech ‘child’s play’, a model for ‘magical’ labour-saving objects such as the PlayPump already exists in Western culture – and more widely: “All productive activities” of the Trobriand islanders, for example, noted the anthropologist Alfred Gell “are measured against the magic-standard, the possibility that the same product might be produced effortlessly” (‘The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology’, in Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 40 – 63, 1992).

But the accomplishment of these powerful messages, which proved so enthralling to audiences to the project, had a negative effect on the functioning of the technology on the ground. In order to preserve the magical appearance of water pumping without a visible connection to work, the PlayPump’s pumping mechanism was hidden within the roundabout. This, writes the team investigating PlayPumps in Mozambique, drastically reduced the pump stroke and so the rate at which it could pump water relative to a conventional handpump. And since the pumping rate was low, children’s play could not provide enough water, and so adults had to turn the roundabout – which is more difficult to use than a handpump. Relying on children’s play – by most people’s definition a voluntary, sporadic activity – for the achievement of an everyday, essential task in resource-poor settings was in itself a gamble. Setting up such a system successfully, if it were possible, would require careful research; and there is no evidence this was done for the PlayPump.

As a result of the PlayPump’s invocation of magical child’s play, adults in Southern Africa were forced to perform a parody of play, to a script that was successful at arousing the interest of first world audiences. Designed for children, the roundabout was at a height appropriate for their use, not for adults. Back pain was reported as a common complaint. Pregnant women and the elderly were not able to use it at all. Some women also felt humiliated at having to use a children’s plaything. Encoding child’s play into the PlayPump rendered it inappropriate for the adults who were compelled to use it; it demanded that they be children, infantalising them both in this quite literal way, and in denying them an informed choice of technology – many wanted the hand pumps back that the PlayPump had replaced.

Presentations

I’ve made a number of presentations about the PlayPump, some of which are shown below. Following the videos I’ve noted sources of criticism of the PlayPump, and provided links to documents (such as UNICEF and the Mozambiquan government’s studies) that you can download.

An Ignite! presentation about the PlayPump (2011) – 5 minutes

Talking about my art-design piece ‘The Problem with the PlayPump‘ at the Science Gallery (2011) – 1.45 minutes

A longer presentation on ‘The Problem with the PlayPump‘, with Prof Patrick Bond (2011) – 1 hour 10 minutes (my presentation the first 30 minutes, followed by Bond)

You can also view an early presentation about my research at the conference ‘PSi16 – Performing Publics’ (2010) over at ralphborland.net/psi16

Africa’s not-so-magic roundabout (2009) – the first negative review of the project in the press, by Andrew Chambers for the Guardian

Viability of PlayPumps (2009) – a statement on PlayPumps from WaterAid, referred to in Chambers article

A series of blog posts (2009 – 2010) by ‘Owen’, who blogged on the PlayPump while a volunteer with Engineers without Borders in Malawi

Troubled Water (2010) – PBS movie and website about the PlayPump, by reporter Amy Costello

Mission Report on the Evaluation of the PlayPumps installed in Mozambique (2008) – study commissioned by the Mozambiquan government (unreleased)

An Evaluation of the PlayPump® Water System as an Appropriate Technology for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programmes (2007) – report by UNICEF (unreleased)

10 Problems with the PlayPump (2011) – an extract from my thesis, drawing on the sources above to identify the main faults in the PlayPump system

Fluid or Frozen: The Zimbabwe Bush Pump vs The PlayPump (2012) – an article I wrote for the blog Design With Africa

Trevor Field of PlayPumps International, J. Eastman, Black and White (2008) – interview with Roundabout Outdoor founder Field (viewed 9 October 2009)

‘The Making of a “Philanthropreneur”‘, by E. Gingerich, The Journal of Values Based Leadership, vol. 1, no. 2 (2008)

Trevor Field interviewed at the William Davidson Institute, University of Michigan (2007) – video (WMV format) (coming soon)

PlayPumps Alliance (c.2006) – USAid document on their partnership with PlayPumps

Mrs. Bush’s Remarks at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Awards (2007) – speech in which Laura Bush mentions the PlayPump

Roundabout Outdoor website c.2005 (screenshot)

PlayPumps International website c.2006 (screenshot)

To improve their lives just add water – leaflet from the HIV/AIDS awareness organisation LoveLife, early partners with the PlayPump (date unknown)

‘The Elephant and the Chili Pepper’, The New York Times, 24 December 2003 – an editorial praising the PlayPump

Coca-Cola Case Study: A waterwheel with a difference – promotional document on Coca-Cola’s partnership with the PlayPump, c.2000

Further sources on the References page