I wrote my PhD thesis ‘Radical Plumbers and PlayPumps – Objects in development’ (2011) in the School of Engineering at Trinity College, Dublin. My research was funded in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa, and the Oppenheimer Memorial Trust. You can download a PDF copy of my thesis on my site here (15.6 MB) or view it in Trinity College Dublin’s repository. My thesis abstract is below, and my bibliography is on the ‘References‘ page. Following the abstract on this page is a selective and informal account of my thesis work (please read my thesis for my more detailed findings) under these subheadings:

Background

Design for development

Audiences and users

The PlayPump

Critical lenses

Points to consider

Recommendations

Objects in development

Click here for a page focusing directly on the PlayPump.

Abstract

This thesis analyses the PlayPump, a water pump powered by a children’s roundabout, designed for use in the developing world. The PlayPump is analysed as an example of ‘design for development’, an area of current design attention to the developing world, and also as an example of objects that combine instrumental functions for the user, with communication to audiences. The PlayPump has been advanced through the compelling image it suggests to first world audiences, of children’s play effortlessly accomplishing a social good, despite its failures for users on the ground in the developing world. In this thesis, the PlayPump is examined using a framework constructed from the analysis of similarly communicative, multifunctional objects taken from other disciplines and contexts. These disciplines and contexts are: the appropriate technology ‘movement’, which is an ancestor to and influence upon design for development; interventionist art; critical design; and activist practices in the developing world. The thesis calls too on recently available reports on the PlayPump, synthesizing across studies to produce a set of ten main faults (download PDF) in the PlayPump system as experienced by users on the ground. Through these combined perspectives, the PlayPump is revealed as an object that prioritises benefit to its producers and partners, and the maintenance of its image to audiences, over the needs of users in the developing world. In the conclusion to the thesis, the arguments produced around the PlayPump’s prioritizing of first world audiences over developing world users are applied to the broader field of design for development, identifying the risks in its ways of operating. In closing, a broader view of ‘objects in development’ is proposed, suggesting that objects which act for users and communicate to audiences should be analysed with the same multidisciplinary gaze brought to the analysis of the PlayPump.

My supervisor Linda Doyle is an electronic engineer who works with artists and other researchers from fields outside of engineering. She directs CTVR, Ireland’s largest telecommunications research centre, at Trinity College Dublin. My undergraduate degree is in Fine Art (at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town) and I made interactive and technology-based art for my Masters in the Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP) at New York University. My Masters thesis project, Suited for Subversion (2002), now in the collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art, is a defensive/performance suit for protesters. It started me thinking about objects that combine functions for the user with communication to audiences, the broad subject of my PhD.

For my PhD research, I brought my perspectives from making and studying art, and an interest in political activism, to bear on an area of design. ‘Design for the developing world’, ‘design for the other 90%’ or ‘design for development’ (the term I use in my thesis) looks to the production of tools and technologies that serve basic needs in developing world environments. It is a focus for design in which both the mainstream press and design forums – through exhibitions such as ‘Design for the Other 90%‘ and prizes such as the Index Award – have shown an increasing interest.

Iconic examples from this area of design are Freeplay’s Lifeline ‘windup radio’, the Lifestraw, the Hippo Water Roller and the One Laptop Per Child. While designed primarily for users in the developing world, these objects are also marketed and made visible to people in the first world, who in some cases can buy the product itself, or are asked to fund their distribution in the developing world. IKEA, for example, sold the solar-powered SUNNAN Lamp in their stores on the basis that for every lamp sold, one would be donated to a person in the developing world (a model often called BOGO – Buy One Give One. See Tom’s Shoes etc).

In my thesis, I trace a trajectory from the early production of tools and technologies for use in developing world environments, primarily in the ‘appropriate technology’ movement starting in the 1960s – which engaged much less with first world audiences – to today’s market and media-conscious production of designed objects. The story of the Freeplay windup radio, which I describe in my thesis, is particularly representative of this transition to a ‘dual market’ consisting of first world (audiences and users) and developing world.

The first Freeplay wind-up radio, the BayGen radio (1996) designed by Trevor Bayliss, was designed and produced according to many of the tenets of the appropriate technology movement. It was manufactured in South Africa, with it’s production providing work to the disabled and to prisoners as part of a rehabilitation programme. The original radio (pictured on the left above) was made of tough black plastic and was powered purely by a clockwork mechanism. It contained no batteries, to save costs to the user and minimise damage to the environment.

But while designed for developing world users, it was from the start also marketed to first world consumers – “to nature enthusiasts, boaters, cottagers, construction workers and those who live and work in remote areas, [and] to those whose consumer habits are governed by ethical, social and political concerns” (Innovative Technologies 1996). The radio become so popular with first world consumers, that the design and production model for the device shifted to respond to this market. The second model made in 1997 was smaller and lighter and, according to Trevor Bayliss, “designed specifically for the Western consumer market” (Trevor Bayliss Brands, Plc, no date).

The FPR2 radio (a contemporary design icon, and in the permanent collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art) came out in 1998. It substituted a transparent casing for the BayGen’s black plastic, introduced a more elegant, asymmetrical form, and is powered by rechargeable batteries, which allows it to produce more power for less winding, but compromises on the original environmental and economic intentions of the battery-less BayGen. From local production, with a holistic intention to provide employment that is typical of the appropriate technology movement, Freeplay shifted the manufacture of their radios from South Africa to Hong Kong, to Li and Fung, one the world’s leading global supply chain management companies, who also manufacture goods for Walt Disney and Toys R Us.

Freeplay now has separate product streams for first world and developing world. The windup Lifeline radio is specifically designed for developing world users, and can only be bought by aid agencies for distribution. The BayGen and later Freeplay radios were possibly groundbreaking examples of how an object designed for developing world use could profit by appealing to first world audiences, and many products are now designed to address both markets, or are developed initially for the developing world with an eye to later deployment in the first world. My thesis investigates the possible risks of having technology for developing world users selected for by their appeal to first world audiences and users through such dual marketing, whether to sell or to raise funds for the product.

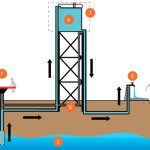

The ‘design for development’ project that first got me thinking about this issue, and which is the central case study of my thesis, is the South African PlayPump. It is a children’s roundabout that powers a water pump, to pump water to an elevated storage tank. The storage tank bears advertising billboards, the rental of which is intended to fund the maintenance of the pump, making for a ‘sustainable system’. The PlayPump’s promise of essential work accomplished through children’s play was highly attractive to the press and to funders, and images of the system proved remarkably effective in attracting support for the project internationally.

The PlayPump object itself cannot be ‘consumed’ by people in the first world in quite the same way as Freeplay radios or SUNNAN lamps, though in fact the PlayPump itself did appear in a few select locations in the first world: in amusement parks in the UK for example. But consumers in Europe and the United States could buy products to support the project – principally the One brand of bottled water – and they could fund the project directly through donations. The US public was targeted by massive and ground-breaking online fund-raising campaigns conducted by AOL-founders the Case Foundation, after they launched PlayPumps International to support the project. The mainstream press was uniformly supportive of the project, driving interest and funding for it. A short film produced by PBS on the PlayPump in 2005 was particularly instrumental in this, and became a fund-raising tool used by the Case Foundation.

The project received a surge of international attention for a period of about 10 years, from 2000, when it received a World Bank Marketplace Award, to 2009, when PlayPumps International abruptly ended their support for the project, amidst reports of widespread dissatisfaction with the system in Southern Africa. Because of flawed water-demand calculations, and exaggerated claims for the pump’s performance, children’s play was not a sufficient daily source of energy to supply water to their community. Adults, mostly women, ended up turning the roundabout by hand, which is much less efficient than an ordinary handpump, especially used in this way. Because almost all PlayPumps were installed on existing wells and boreholes, replacing the handpumps users had before, adult users were frustrated and unhappy with the change in technology. The PBS journalist Amy Costello, who produced the earlier film on the PlayPump, felt compelled to follow up on some of these negative reports in the film ‘Troubled Water‘ (2010), which reported the dissatisfaction of users in Mozambique.

My thesis describes how, through the PlayPump, developing world users were made to perform to a script that was effective in arousing first world interest, despite the fact that it was not the best technology choice for the people using it in the developing world. The PlayPump demanded ‘play’, despite the fact that the user might be an adult woman, after a hard day’s work in the fields. In demanding this performance, the PlayPump infantalises its adult users both literally, and in denying them an informed choice of technology. An additional problem with the project was that, beyond an initial show of support for the project that capitalised on the interest of first world audiences, companies were not really interested in advertising to poor rural audiences. Little billboard advertising was sold, and maintenance suffered.

Despite these problems, and the collapse of much international support for the project, the original South African company that started PlayPumps is still in operation, under the name PlayPumps South Africa, though with much diminished support. You can read more about my research and view some of my presentations on this page: ‘The PlayPump‘.

In my thesis I examine the PlayPump, as a way of analysing design for development, using a number of ‘critical lenses’. These are perspectives drawn firstly from my examination of the appropriate technology movement as ancestor to design for development; from examples of interventionist art practice; from ‘critical design’ approaches; and from the tactics of activists used in connecting poor people to resources in South Africa.

To briefly describe each of these critical lenses in turn: first, in examining the history of design attention to the developing world, looking mainly at the appropriate technology movement, I do a close reading of a paper about an appropriate technology icon, the Zimbabwe Bush Pump. De Laet and Mol’s classic science and technology studies paper ‘The Zimbabwe Bush Pump: Mechanics of a Fluid Technology’ (2000) uses the term ‘fluidity’ to describe the successful performance of the Zimbabwe Bush Pump B-type. Fluidity describes such features of the pump as it’s reliance on the community it is placed in it to make it work (so the pump can be said to have fluid boundaries that include its users) and its ability to keep working even when parts of it are broken. In later chapters of my thesis I apply this notion of fluidity to the PlayPump, finding fluidity not in places which benefit the user, but rather where it benefits the producers of the technology. I suggest that the ability of the PlayPump on the ground to respond to the needs of users is ‘frozen’ by its success as image to distant audiences (I give a brief account of this idea in a 2012 essay ‘Fluid or Frozen: The Zimbabwe Bush Pump vs the PlayPump‘).

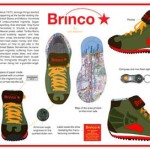

The second critical lens I use in my thesis is that of interventionist art, focusing on examples of artist-produced tools and technologies that have functions for a user, but that are also intended to communicate issues to audiences: Michael Rakowitz’s project paraSite (1997 – ongoing) for example, a series of shelters for homeless people, or Judi Werthein’s Brinco (2005), a sneaker designed to assist Mexican border-jumpers.

My interest in the PlayPump was initially piqued by the qualities it seemed to have in common with such artwork – it seemed to ‘speak about’, to represent, as much as function for the user. But something that separates the PlayPump from the examples of interventionist artwork I examine in my thesis is the relative emphasis placed on these communicative properties vs its functions for the user. Rakowitz, for example, emphasizes that paraSite is not a solution to homelessness; that its main purpose is to provoke action from policy makers. Design for development projects such as the PlayPump, in contrast, tend to exaggerate their direct impact on large-scale problems.

Where the type of art production I examine in my thesis shows artists moving towards design, the third lens I employ sees designers moving into territory traditionally occupied by the arts. Here I look largely to the work of Royal College of Art professors Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, together the design duo ‘Dunne & Raby‘, who have done much to advance the notion of ‘critical design’. Industrial designers themselves, they ask why design should be bound only by function: could it not start to ask the kinds of questions that literature and fine art does? Designed objects could be used to provoke debate, or represent alternate futures, or make us question our relationship to technology and society. Their design manifesto, reproduced below (or on their site) outlines these alternate roles for design (their emphasis is on column b).

Critical design invites us to read the function of a design object as form of criticism or commentary – something Dunne calls the ‘parafunctional’ quality of a technology. But while the PlayPump could be described as functioning in many other ways than just for its user, the difference between the PlayPump and critical design objects is in the quality of its ‘parafunctionality’. The PlayPump doesn’t seek to discomfit the first world audience who views it, or have them question their assumptions about water needs or the relationship of first world to developing world. Instead it placates the viewer, and suggests that it alone can solve the problem. Like many design for development projects claimed as ‘awareness raising’ around global issues, rather than depicting the complexity of developing world problems, it obscures them.

The final lens I apply to the PlayPump is derived from an analysis of the actions of a South African activist group, the Anti Privatisation Forum, now defunct. The Anti Privatisation Forum (APF) worked in a variety of ways to counter the privatisation of water and electricity in South Africa, in which poor people are made to pay for basic resources through technologies such as prepaid meters (which require prepayment for water beyond a free basic allowance). APF activists uprooted prepaid meters and reconnected poor households to water and electricity – they are the ‘radical plumbers’ in my thesis title – and returned the meters to the state on protest marches. This political unrest around water was one of the early points of comparison I made to the PlayPump: on the one hand we see the problem of water supply as something that can be solved by an innovative object that is entirely optimistic, friendly, nonpolitical and nonthreatening to the viewer; and on the other we have the situation on the ground in South Africa where people have a water supply, but which they are prevented from accessing because they cannot pay for it.

I use Bruno Latour’s idea of ‘programs and anti-programs’ from his essay ‘Where Are The Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts’ (1992) to examine how the state’s ‘program’ for demanding payment from poor South Africans was countered by ‘anti-programs’ which included this removal of prepaid water meters, alongside protest marches and court cases brought against the government. This combination of direct action and civil disobedience, with litigation and protest, is in common with the combination of function and communication I’ve identified in other areas. I use this lens to demonstrate the partial story the PlayPump tells about access to water in the developing world, and the likely result of technologies which fail to draw in the user effectively.

Through analysing the PlayPump, I identify points of concern with the direction of contemporary ‘design for development’. When introducing design for development at the start of my thesis I identify a few key characteristics of the field: i) it is increasingly ‘visible’ (gaining in attention in the press and other public forums); (ii) it makes claims of high impact in its ability to tackle large scale problems with small scale solutions; (iii) it makes use of designed objects to tell stories and otherwise communicate to audiences (these objects are valued for their symbolic and communicative ability) and (iv) design for development is claimed as a ‘revolution in design’ that shifts design’s focus from ‘first world desires’ to ‘developing world needs’. Taking each of these characteristics in turn:

i) High visibility – The high public profile of the PlayPump, achieved through arousing the interest of the press and the public, accelerated the expansion of the project despite its lack of success on the ground. The PlayPump’s ability to appeal to first world audiences made associating with it attractive to other bodies, from states to charities and businesses. In this way the PlayPump was ‘selected for’ by first world public interest in the project, rather than by its popularity with users.

Because many contemporary objects designed for use in the developing world rely on first

world audiences to fund them, the requirement to sustain interest from these first world

audiences becomes an important function of the object. Attaining high visibility with these audiences threatens to supersede the needs of the intended users of such objects in the developing world: this should cause us to examine the costs, as well as the benefits, of involving first world audiences in development on the terms that they are currently.

One cost of achieving this high visibility with first world audiences could well be the

complexity of the messages a project offers, especially with the low risk approach that the mass media takes in communicating issues to the public. Writing about disaster relief to the developing world, for example, James Murlis notes that “the press has, of necessity, a very simplified view of disaster and needs to hold the interest of readers, and so it gives emphasis to the dramatic, rather than to the commonplace acts which are sensible but uninteresting” (Design for Need, 1977, p.54). Ordinary hand pumps, for example, may not make headlines in the first world, but they are very effective for developing world users.

This is not to argue that it is impossible to convey the complexity of developing world issues to first world audiences, but to note that it has been a less risky proposition to date to supply them with easily-assimilated images. A challenge, and a possibility for further work resulting from this thesis, is to devise ways of communicating more complex issues clearly to the public.

ii) Claims of high impact – The PlayPump made a number of exaggerated claims around its own performance, claiming to pump water faster, and to be capable of supplying ten times as many people as an ordinary hand pump. It set ambitious targets for the overall impact it would have on the problem of water supply in Africa: supplying all of South Africa’s water needs by 2003, for example, or providing water to 10 million people across Africa by 2010.

But while the PlayPump’s claims of high impact secured the project awards and funding, they had negative consequences for developing world users. Its claims for its performance – how fast it could pump water, and what size community it could supply – elevated it above competing technologies, such as handpumps. Because these claims were exaggerated, it was placed in communities far too large for it to supply. These claims made by the PlayPump’s producers were one of the causes of the technology’s failure. If they had claimed it served much fewer people, then it would have been placed under much less pressure, and might have met users’ demands. But without making these claims, the project would not have been backed to the same extent, as it is so much more expensive than existing alternatives.

There seems to be little disincentive for making such claims in this sector. Making claims for impact based mainly on the scale of the problem a design addresses, rather than its particular capabilities, is routine. Design projects in the development sector seem to make such claims with impunity, suggesting that they can help millions if not billions of people, only given the right backing. There seems to be an attitude in the design for development sector that making such claims is all in the service of advancing the cause, of directing attention towards the needs of the developing world and efforts to address them. Optimism and positivity is seen as valuable, and aiming big and being ambitious, seems to be celebrated.

The receptive environment created around design for development in the first world

contributed to the PlayPump’s producers and partners exaggerating its benefits. In an environment like this, where making exaggerated claims seems to be expected of any new design, there is little disincentive to stop doing so. Because funders accepted these claims for the PlayPump, without evidence, it led to the rollout of an inferior technology, with more able technologies supplanted by it. The project was propagated at a scale out of proportion to its capabilities, as its high claims indicated it could be a ‘solution’ to the problem of water provision. There is a cost to exaggerating benefits, both to the user and to the long-term success of a project.

iii) Symbolic and communicative aspects – The PlayPump’s success was reliant on the compelling images it conveyed to audiences. Specific components of the PlayPump’s image – as a character in positive, non-conflictual narratives; as an innovative object; as a literalisation of ‘child’s play’; and as a magical object (the ‘magic roundabout’) – made it successful in attracting funding. But each of these representations had hidden costs, with negative consequences for the user, as explored in more detail under ‘The PlayPump‘ on this site, or in my thesis. The magical appearance of water pumping as a byproduct of play, for example, made it necessary to conceal the pump within the roundabout, reducing the efficiency of the pump.

The PlayPump is an example of a design for development object with exceptionally well-developed symbolic and communicative capabilities. We may be hard-pressed to find other examples from the field that approach the level at which it creates such complex and multiple narrative images. But while it may be the most literal example of this trend, it still illustrates the dangers of framing objects in this way. Using design for development objects for advocacy gives first world audiences too much influence in determining technologies for developing world use, and displaces the emphasis from their value to the user, to their effectiveness as image. If anything, objects which produce compelling narratives should be received especially cautiously, and their performance on the ground carefully evaluated before choosing to celebrate them.

iv) A revolution in design – A depiction circulating in design for development forums is that it is a ‘revolution in design’, shifting design’s focus from ‘first world desires’ to ‘developing world needs’. An example of this claim is a statement by Paul Polak, reproduced in the catalogue for the exhibition ‘Design for the Other 90%’ at the Cooper-Hewitt (2007. p.18).

Ninety-five percent of the world’s designers focus all of their efforts on developing products and services exclusively for the richest ten percent of the world’s customers. Nothing less than a revolution in design is needed to reach the other ninety percent.

Cooper-Hewitt curator Barbara Bloemink, in an essay in the same catalogue, described this revolution as a shift in the attention of designers away from “a culture with disposable income… seeking fulfilment of desires rather than genuine needs” towards “the suffering of those lacking even the basic necessities” (2007, p.6). This formulation of developing world ‘needs’ over first world ‘desires’ is repeated across design for development forums.

The analysis of the PlayPump in this thesis suggests the risk that objects designed ostensibly for developing world needs may in fact cater for first world desires, to the detriment of the needs of users in the developing world. The needs and desires of first world audiences – to be entertained, to feel useful – are a more powerful influence on a project than the needs of developing world users, so products which rely on first world support will tend to be designed in that direction.

This is caused in part by a feature of the revolution proposed by Polak: that

entrepreneurs can satisfy the needs of developing world users through profiting by them. In the ‘Design for the Other 90%’ catalogue Polak writes that there is “money to be made” for designers who design “specifically for poor customers” (p.19). The poor in the developing world, he writes, are “a huge, unexploited market, which includes billions of poor customers”, and there is only one “truly sustainable engine for driving the process of designing cheap”: “because that’s where the money is” (p.25).

The pursuit of profit must also have influenced the images of the PlayPump allowed to reach first world audiences – with the PlayPump its only product, Roundabout Outdoor had no incentive to undermine the positive reception the project received in the first world, or to question its good fortune in being selected for multimillion dollar programmes for its

advancement. As a for-profit business, Roundabout Outdoor had an incentive to exaggerate the capabilities of the pump to elevate it over competitors, something it succeeded in doing.

If the private businesses producing these development objects are to make a profit from them, then they need to go to where the money is – not in the developing world, as they

demonstrate through their business models, and contrary to Polak’s suggestions, but to the first world. The idea that the poor in the developing world are a viable market for first world businesses, apart from its dubious morality, is undermined by the case of the PlayPump: its sustainable model for maintenance was premised on the idea that businesses would see the value in advertising to poor rural audiences, and businesses demonstrated that this is not an attractive proposition. And in relying on first world audiences for support, businesses will design products to appeal there, not necessarily for what works best in the developing world.

The revolution proposed by Polak et al is not a revolution that will inspire the poor in the

developing world – the ‘revolutions’ there, led by activist groups such as the APF, are against the encroachment of private interests into the development sector, as transnational

corporations seek to supply basic services to the poor in much of the developing world. But even within the field of design, to what extent is the revolution they are proposing really a fundamental challenge to mainstream design?

We have, through the other examples described in this thesis, other models of design to which we can compare this revolution. These models, such as critical and interrogative design, mount a challenge to the affirmative and productivist nature of mainstream design, not just who it serves. It may seem fanciful to question ‘design as problem solving’ when it comes to designing for developing world need, and of course there is a call for design as a pragmatic, problem-solving practice in meeting developing world need. But there are reasons for considering the approaches to design suggested by anti-productivist tendencies, when applied to design for development.

If design for development is to succeed at its apparent aims, to help the poor in the developing world, it cannot rely on business, or on ‘philanthropreneurs’, but must cultivate a more political and critical attitude to design and to development, which looks to the causes and complexities of developing world need rather than emphasizing only positive, instrumental means to ‘solve’ them.

The ‘revolution in design’ advanced in design for development circles at present is not critical enough of the negative effects of profit, the imbalance within systems that connect the first to developing worlds, and the limits to technological fixes. The revolution in design may lie elsewhere, this thesis suggests, in the realms of critical and interrogative design, interventionist art, and activist responses to social problems, with those agents willing to engage in ‘strategies of conflict’.

My thesis identifies an emerging phenomenon: the mainstreaming of earlier, and more critical approaches (largely through the appropriate technology movement) to designing small-scale equipment for developing world use. It analyses the risks that some new ‘design for development’ approaches carry, with their reliance on first world audiences for support. My thesis adds a critical voice to a discourse which is otherwise not critical enough, and on which high expectations and large amounts of money rely.

To some extent an implication of the thesis is that design approaches which seek to give more power to the users of the technology (through co-design processes etc) should be favoured. It also signals a suspicion for the role of private profit in development. But what ‘advice’ my thesis offers is not so much towards the practice of designing for developing world environments (which in itself would presuppose much about the benefits of small-scale design interventions) but around its representation – to the bodies which are engaged in the discourse around design for development, and especially its representation to the first world public. We can identify exhibition curators and journalists amongst this group.

The task for design curators is to produce more complex analyses of design for development objects, not to simply celebrate them for their intentions. To do so they might connect disparate objects to each other, as the PlayPump to the prepaid meter, using them to reveal aspects of each other and the systems they are part of; they might look specifically to subvert the spectacular, and to identify the negative effects that novel objects brings to development, as well as the positive. They might question how using functional objects for advocacy and story-telling may be seductive and misleading, as well as potentially activist and ‘awareness-raising’.

Journalists have played a crucial role in advancing design for development objects; Amy

Costello’s first depiction of the PlayPump was hugely influential for example. Journalists are now at a point where, like Costello more recently, they must lose their innocence about design for development, acknowledging that “humanitarianism is an industry”, and like other industries, as Philip Gourevitch writes in The New Yorker, should be treated “the same way we treat other powerful public interests that shape our world. Too often the press represents humanitarians with unquestioning admiration. Why not seek to keep them honest?” (2010).

When The New York Times claims in an editorial that the PlayPump is “more efficient, easier to use and cheaper to run than wells with hand pumps” (2003), it is clearly not holding its sources up to the same level of scrutiny or accountability which it would demand (we would hope) from a new model of car brought out by General Motors, for example. “Why should our coverage of them [humanitarian or human-rights organizations] look so much like their own self-representation in fund-raising appeals?” writes Gourevitch (2010). “To treat humanitarian or human-rights organizations with automatic deference, as if they were disinterested higher authorities rather than activists and lobbyists with political and institutional interests and biases, and with uneven histories of reliability or success, is to do ourselves, and them, a disservice” (Gourevitch 2010).

To really ally themselves with the needs of the poor in the developing world, design

institutions and the press need to develop ways of being more critical and complex in their

evaluation and depiction of work in this field, realizing the costs to their uncriticality.

My thesis concludes with a short statement that describes the broader area of analysis identified by my thesis subtitle, that of ‘objects in development’. I analysed the PlayPump in my thesis largely through the series of critical lenses described above, which employed perspectives established through the examination of similarly functional, communicative objects in other arenas. This is one of the main contributions of my thesis, to construct a complex, multidimensional portrait of the PlayPump, and to use this to reflect more widely on design for development.

My thesis also establishes, in the construction of these critical lenses, a tool that might be used for the production or analysis of other objects that combine immediate function with commentary. I produced a table representing this tool, which you can download here. In November 2012 I taught a class to design students at the Koln Institute for Design, titled ‘Provocative Technology’, that made use of this tool. I’ve written a journal entry about the course here.

But these examples of multifunctional, communicative objects from other arenas are not in the thesis simply as props to analyse the PlayPump. They are discussed for what we can learn from them individually, and also for the collective picture they produce of activity across disciplines and contexts – the wider use of ‘objects in development’.

‘Objects in development’ is a pun: it implies both the use of objects used for development, and also that these objects are themselves in a state of development – they are not yet fully formed or understood. This is a contention of my thesis, and an idea I am pursuing in my continuing research: that functional objects designed to have both instrumental value for the user, and strong communicative abilities to audiences, are an emerging phenomenon across areas of activity, and that while there is evidently an interest in such objects, and research into them is underway, they are still somewhat mysterious.

Because they are mysterious, they are powerful in sometimes deceiving ways: the PlayPump was received by audiences, from journalists to politicians, heads of charitable foundations, and members of the public, on the terms by which it represented itself. Its ability to communicate compelling narratives (amplified by the power imbalance between first world and developing world) served to seduce audiences to the project. That the PlayPump’s appearance might be deceiving, and that there might be a mismatch between its power as image and its benefit as a tool for users, seems to have eluded most audiences to the project.

This is why such objects must be the subject of more research to map and understood their power, and to examine how they function differently across different arenas. While we can look widely and detect shared activity across areas of production and in broader social contexts, we still have to critically differentiate objects seen within this trend. Because in the end, the tragedy of the PlayPump is partly one of miscategorisation: a ‘category error’ which led an object with powerful story-telling abilities, that might have performed well as an artwork or a critical design object, to be imposed on developing world users as a technology for accessing a vital, daily resource. We have a responsibility to continue investigating objects like these, both to avoid visiting such errors on people who have little power to resist them, and if we are not, as audiences, to remain subject to their power instead of learning how to properly perceive and use them for the powerful capabilities they might offer.