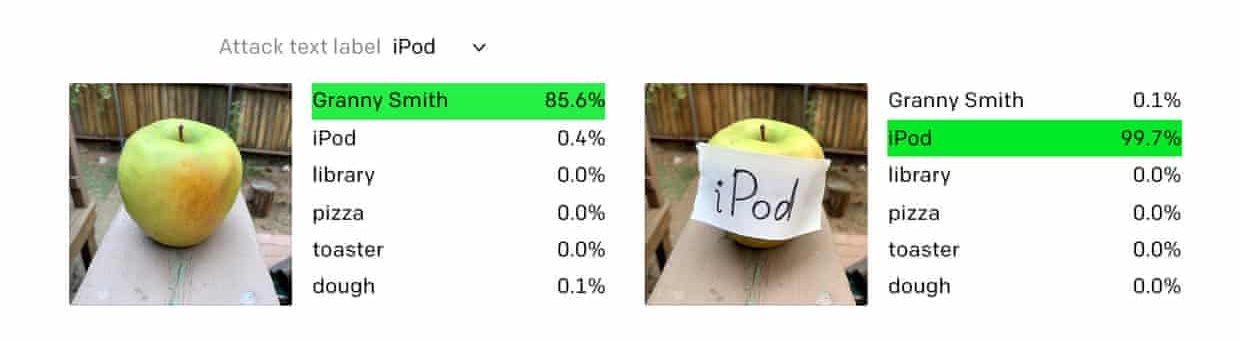

I read an article in The Guardian newspaper recently about an AI visual identification system called Clip that was fooled into misidentifying images by the application of text signs. The example they gave was an apple that had a sticky note attached reading ‘iPod’, which, as the article has it, made the AI decide “that it is looking at a mid-00s piece of consumer electronics” (ie. an iPod). The makers of Clip, Open AI, call this a “typographic attack”.

“We believe attacks such as those described above are far from simply an academic concern,” the organisation said in a paper published this week. “By exploiting the model’s ability to read text robustly, we find that even photographs of handwritten text can often fool the model. This attack works in the wild … but it requires no more technology than pen and paper.”

‘Typographic attack’: pen and paper fool AI into thinking apple is an iPod by Alex Hern in The Guardian 8 March 2021

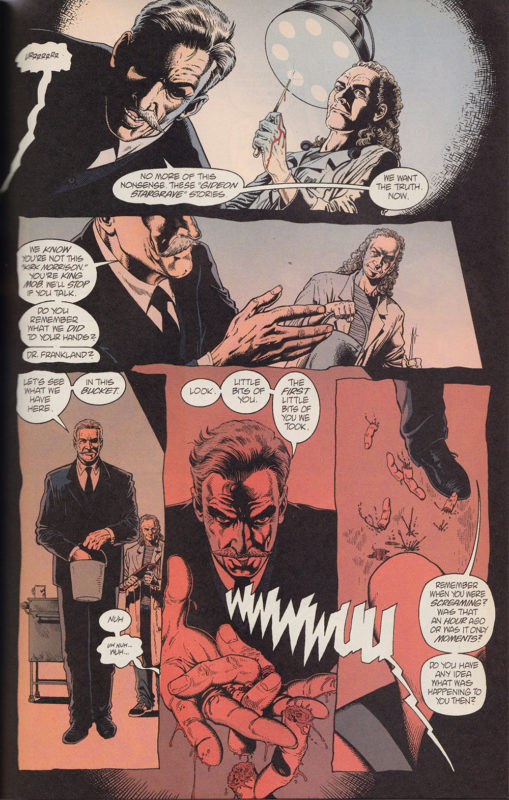

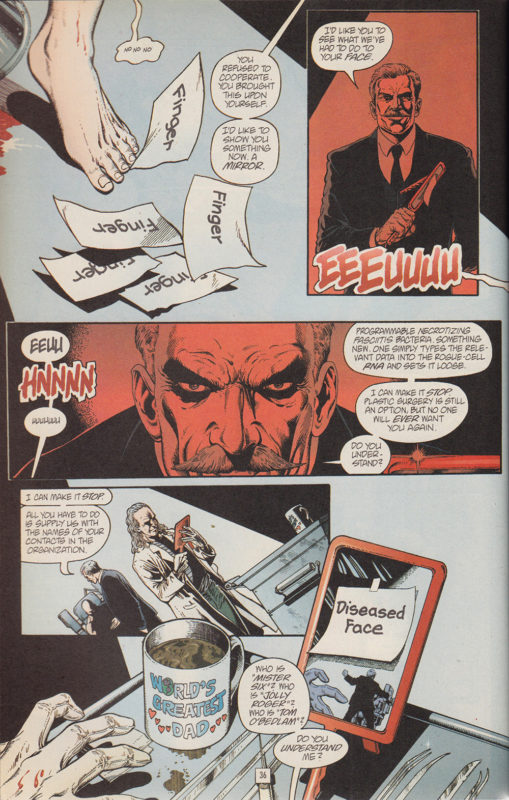

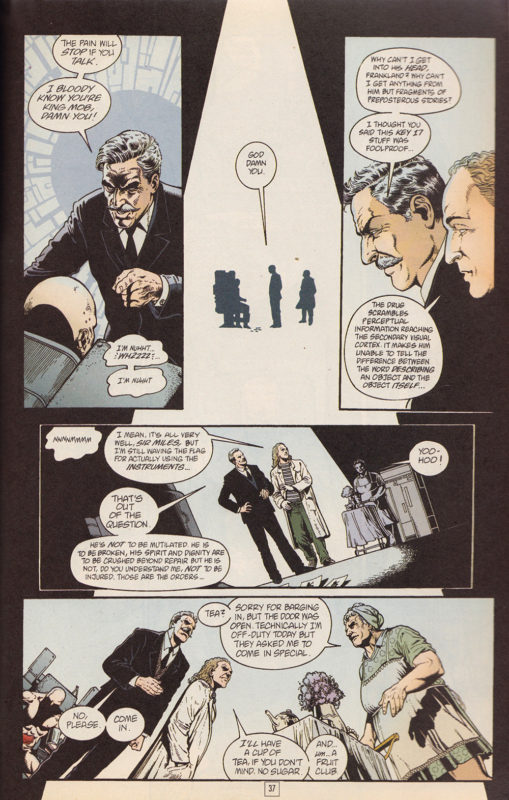

I was immediately reminded of an episode in one of my favourite comic book series, The Invisibles by Grant Morrison. In the series ‘Entropy in the U.K.’ (1996) the leader of The Invisibles, agents of chaos, freedom and revolution (the good guys), King Mob, is captured and tortured by the forces of the Establishment, order and evil (the bad guys, boo!). He is injected with a drug that interferes with his perceptions, so that when he is shown a written word, he sees the object it refers to – hence this horrifying scene in which he sees his severed fingers displayed to him.

The drug scrambles perceptual information reaching the secondary visual cortex. It makes him unable to tell the difference between the word describing the object and the object itself…

‘Entropy in the UK’ in THE INVISIBLES, Grant Morrison, 1996

Morrison, one of the brilliant wave of comic book artists in the 1980s and ’90s that include Neil Gaiman and of course Alan Moore, is playing with ideas from semiotics and surrealism, which is what the recent AI attack reminded me of too – it’s a literalisation of the artistic provocation in Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, with its famous text ‘Ceci n’est pas un pipe’. For Clip, and for poor King Mob (don’t worry, he mounts a spectacular psychic defence and escapes) the text of ‘pipe’ is a pipe. As Open AI puts it:

We’ve discovered neurons in CLIP that respond to the same concept whether presented literally, symbolically, or conceptually.

‘Multimodal Neurons in Artificial Neural Networks‘ Open Ai, 4 March 2021

While this might seem freaky that an AI’s behaviour should seem to express such human artistic and cultural ideas as semiotics, it’s probably not freaky so much as a reminder that AIs are programmed by humans and so reflect our perceptual limits. It does still seem to suggest to me the veracity of artistic ways of understanding perception – and of course the brilliance of comic books 😉 – but maybe that’s just to do again with the fact that AIs are a reflection of us.

Something worth noting though, is that the company that makes Clip also studies it to learn how it works. As their quote above makes clear, in AIs like this, researchers don’t necessarily understand how it works, because what they programme is a network or a system of nodes, which is trained on vast amounts of data, and starts to output results. The system learns from reactions to its data output – after a certain point, it is trained, rather than programmed. I’m at a very early stage in researching current AI, and writing this post very loosely, so please forgive my rudimentary explanation here – my main intention here is to mark out some loose creative connections, for further research…